Charles Allen Du Val

His life and works

London Season 1886-1888

Charles Henry Du Val arrived back in England from his overseas tour in February 1886.

He and his wife Minnie had given up their house in Dublin and they settled in Blackheath in London. Charley announced a new book Punkah Waftings : A Journal of Eastern Experiences. No copies are known to have survived, however, and perhaps it was never written.

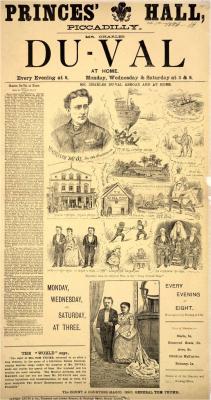

In July 1886 the press announced that "Mr. Charles Duval, having returned from his tour through South Africa and India, will make his reappearance at the Prince's Hall, Piccadilly, on Monday, August 2nd, when he will give his popular entertainment of 'Odds and Ends'. " (1). Charles Henry Du Val gave many performances at the Princes’ Hall with great success until December 1886, and then transferred the show to other London venues where it was no less popular. The show by then included acts by a variety of other performers introduced by Charley.

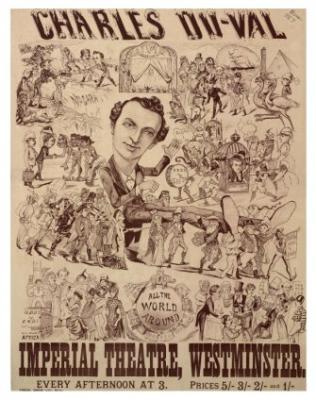

Poster dated 1 October 1886

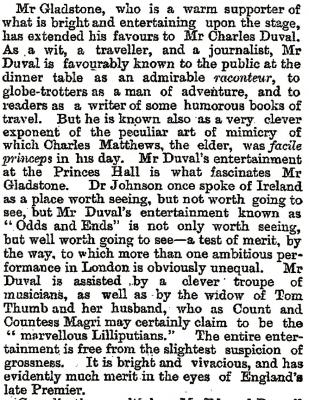

Aberdeen Weekly Journal 26 August 1886

(2)

(3)

The Era London 11 September 1886 (4)

MR. CHARLES DU VAL "AT HOME."

Mr Charles Du Val was "at home " to the musical profession at the Prince's Hall last Monday afternoon and many members of the theatrical profession also availed themselves of his kind invitation. The popularity the versatile entertainer has been so long established, and the main features of his "musical monologue" are so widely known, that it is rather going over old ground to enumerate its items. Mr Du Val however, shows a laudable desire to bring his entertainment "up to date," both by the introduction of new details into his own part of the "show" and by the engagement of clever supplementary performers. On Monday afternoon he commenced the former by his admirable recitation of "The Bells." Besides giving a capital reading of the poem from an elocutionary point of view, he imitated the tones and timbres of the different kinds of bells described in Poe's verses very effectively and musically.

He next impersonated cleverly one Signor Howlini, a tenor "who relies principally upon his upper notes and his black moustache." His singing of "Maid of Athens" was very little more affected than that of many a real tenor singer, and it seemed to us that a considerable fraction of the audience were enjoying the ballad seriously. Then we were introduced to Colonel Peppard, a pompous and cynical old Indian officer, from behind whose newspaper presently emerged Mr Du Val, having altered his appearance (without leaving the stage) to that of a "masher" of the day, “Chawley,” of course, with the song "Leaning on a Balcony."

(5)

A complete contrast to this characterisation was Mr Du Val’s embodiment of Mrs Clearstarch, an Irish washerwoman, who hung out real clothes on a real line whilst delivering herself on various domestic subjects. Perhaps the cleverest of all Mr Du Val’s imitations was that of Miss Bella Dashaway, the "Belle of the Ball," in which character he sang a mezzo-soprano song with all the minauderies of a real female vocalist. As Professor Dullbore, F.I.G.S.X.Y.Z., Mr Du Val delivered a burlesque lecture on Science, his assumed seriousness exciting much mirth, and the Professor's surprise and annoyance at its expression being comically simulated. Mr Du Val also, by the aid of a "divided skirt" and wig, which showed on one side the flaxen locks and blue gown of Marguerite and on the other the black curls and cloak of Faust, and assisted by a quickly-removable hooked nose and quaint scalp for Mephistopheles, transformed himself from one character of the trio to another at a second's notice. accompanying the transition with appropriate recitatives and solos.

Another clever notion was an exact imitation of those " big-headed " sketches of celebrities sometimes seen. This was done by means of an easel and a series of full-length paintings from which the face had been removed, to be supplied by Mr Du Val's mobile features with various different embellishments. "Speaking likenesses" of Mr Henry Irving, Sir Garnet Wolseley, Lord Randolph Churchill, and others, were thus produced.

The selections chosen by Mr Du Val on Monday were taken from a repertoire including seventeen separate items. The interval between the two parts was filled by the Circassian Glinka Family, whose white locks made their appearance noticeable, and who performed very cleverly on the violin and cornet.

We have reserved to the last our account of Mr C. and Miss Lillian Moritt's thought-transference feats. Miss Moritt seated herself on a chair on the stage, and was blind-folded by Mr Du Val, the option of performing the operation being offered to anyone in the audience. Her brother then took up his position in the body of the hall, and a member of the audience conveyed in a low whisper to him the number on a coin. Miss Moritt, after some preliminary movements of her hand and fingers, then rose, and, going to a blackboard at the back of the stage, wrote slowly the correct figures. In exactly the same manner she wrote the number of a cheque, 341940, the cypher being omitted, as the line of figures already extended to the edge of the board. The difficult word "Zeus" being chosen by someone in the audience and whispered to Mr Moritt, his sister wrote it down after some consideration, merely repeating the "Z" at the end of the word, so that it read "Zeusz." She also drew from a pack of cards the one selected, and placed four cards taken from a pack on a chair exactly as desired. Mr Du Val challenged the audience at the conclusion of the exhibition to guess "how it was done." The only weak point in the chain of evidence supporting the genuineness of the "thought transference" was (obviously) the non-disproval of the assumption that the persons who gave the name, numbers, &c., were not confederates of the performers. This doubt dispelled, the trick or phenomena would be surprisingly complete. The silence preserved during the exhibition and the distance of the supposed thought-transferer from the alleged recipient added to the difficulty of detecting the secret, a task which we leave to Mr Du Val's and Mr and Miss Moritt's future patrons (6).

Charley Du Val also gave matinee performances of his show at the Imperial Theatre, and transferred his show the the St James's Hall on 6 December 1886 (7).

However, in 1887 the show had to stop when Charles Henry Du Val became ill with laryngitis. Fearing that his voice would be damaged, his doctors advised a prolonged rest from performing on stage.

But Charley continued to write, producing press reports and fresh songs and sketches for his show with new characters.

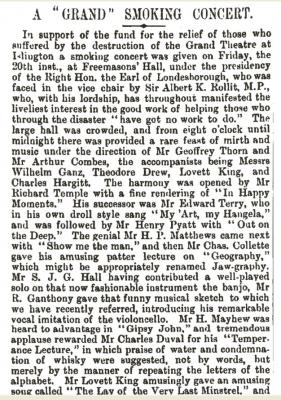

By the end of 1887 he was well enough to return to the stage, and early in 1888 he took a small (but very much appreciated) part in a charity performance in aid of those who had suffered in the destruction by fire of the Grand Theatre in Islington, London (8).

In 1888 Charles Henry Du Val began planning an enormous worldwide tour, which was to start in South Africa, then going on to Madagascar, Mauritius, Ceylon, India, Burma, Malaya, China, Japan and the United States.

After that there was to be another London season.

(1) The Graphic London Saturday 24 July 1886.

(2) The Aberdeen Weekly Journal was here at fault. It was not Ireland as a whole but the Giant's Causeway that Dr Johnson spoke of as "Worth seeing? yes; but not worth going to see." Oxford Dictionary of Quotations 3rd edition (1985) page 278.

(3) General Tom Thumb was the stage name of Charles Sherwood Stratton (1838-1883), a midget who achieved great fame with the showman P.T. Barnum. He became a freemason in 1862 in a ceremony performed by a man over twice his height. In 1863 he married Lavinia Warren (1841-1919), a lady of similar stature.

Two years after her husband's death she married Count Primo Magri, an Italian dwarf. He had a twin brother of similar height, Baron Magri. In 1914 Count and Countess Magri appeared together in a silent film The Lilliputian's Courtship. She wrote her memoirs entitled The Autobiography of Mrs Tom Thumb.

(4) Chang the Chinese Giant was the stage name of Chang Wu Gow (1840s-1893). He was about eight feet tall. He began appearing, with his Chinese-born wife, in London in the 1860s and afterwards toured widely. Well educated, he spoke many languages. After his wife died he married English-born Catherine Santley. In 1878 Chang retired from the stage, and set up a Chinese tea and curio shop in Bournemouth, where he died aged only fifty in 1893.

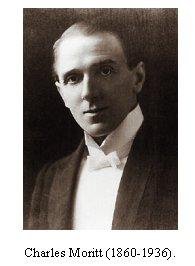

(5) Charles Moritt was a very clever Yorkshireman who deserves to be far better known. Aged only 18, and inspired by the Davenport Brothers (American magicians claiming supernatural assistance), he made his own magical cabinet and gave a two hour show in Selby featuring mind-reading and a disappearing act. He quickly found work at the Leeds City Varieties Music Hall, and soon became an impresario.

Lillian Moritt, although presented as such, was not his sister. Her real name was Ada. They perfected a “mind-reading” trick that baffled other magicians because their coded communication did not rely on particular words in Charles's patter, but on the precise pauses between them. He specialised in making members of his audiences disappear, and taught Houdini the famous Vanishing Elephant trick.

(6) The Era London 23 October 1886. Also reported in the Pall Mall Gazette of the same date.

(7) The Era London 4 December 1886. The Imperial Theatre was demolished in 1907. It had adjoined the Royal Aquarium, which opened in 1876 but was closed and demolished in 1903. Both were replaced by the present Central Hall, Westminster.

(8) The Era London 28 January 1888. The Grand Theatre, Islington was designed by the architect Frank Matcham. It opened in 1883, replacing an earlier theatre, but was destroyed by fire on 29 December 1887.

For a collection of the press reports on Charles Henry Du Val see Charles Henry Du Val Press Cuttings.