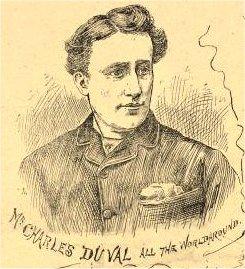

Charles Allen Du Val

His life and works

Overseas Tour 1885-1886

Outward Bound (1)

Having completed his London season in the early summer of 1885, Charles Henry Du Val sailed on the Union steamship Trojan on 31 July 1885, for another South African tour.

This time he was accompanied by his wife Minnie. Madeline was left behind in the care of her aunt.

Bay of Biscay

Suez Canal

Charley in Arabia

Port Louis Theatre, Mauritius

However it was not a good time to have chosen. South Africa was in a deep recession that was to last until the gold discoveries made on the Rand could be exploited fully. There were many commercial failures, particularly in the Transvaal, and there was little to encourage touring in the interior of the country.

Charley and Minnie and their team had a warm welcome from their old friends wherever they travelled, but performing over an extended season was pointless. Shows were given in Cape Town, but they only remained there for one week. Then on by train to Kimberley, where the financial situation was no better. Only three performances were given, and they returned to Cape Town with two stops. Then a short tour of Cape Province, before taking ship to Port Elizabeth and a few concerts in Natal. Then in October 1885 they sailed in the Castle Line steamship Taymouth Castle for Mauritius, Ceylon and India, where they had greater success (2).

After they had arrived back in London, Charley gave a press interview about his travels which was published in May 1886 with four woodcuts illustrations from photographs that he had taken (3):

“A SHOWMAN’S TRAVELS IN AFRICA AND ASIA : AN INTERVIEW WITH MR. CHARLES DU VAL

It would be impossible to reproduce here a tithe of the interesting things that Mr. Du Val has to say concerning his recent travels. Of course every one has read or heard of the famous entertainer at one time or another. He has written books, edited a newspaper, travelled over a large portion of the earth's surface, fought, and, better still, bled for his country and his Queen. He is a monologuist, and is troubled by no golden-haired ladies and blue-chinned gentleman. An evening suit, a dozen or two changes, a score of wigs, a pair of curtains, a table, a glass of water, and there you are. He is here today and gone to-morrow, if it so pleases him. Sometimes he fancies a trip to the other side of the world, rings the bell for the table, sends his servant to take a berth, packs up his luggage, and disappears to see fresh sights and conquer new worlds. Wherever he goes he is welcomed as a bon camarade. One shipboard every one, from the cook to the captain (who are of equal importance), bows before him. The passengers look upon him with great respect, as one who has breathed the mystic perfumes of the footlights. He, in return, gives them odds and ends from his repertoire in the smoking-room after dinner. Ashore he is asked everywhere, and life is made very agreeable. All he asks for is good houses. He sees everything, he goes everywhere. This is Mr. Du Val’s case. Some eight or nine months ago he packed up his traps, engaged an assistant, bought a camera pour s’amuser, and took the steamer to his old hunting-ground – the Cape. And now Mr. Du Val is back in London again, after journeying over land and water some 22,000 miles, and, we hope, with as many pounds in his pocket as the result of his labours. That, however, is mere conjecture.

Cape Town has, of course, an excellent theatre, and Kimberley, Durban, Maritzburg, Port Elizabeth, and Grahamstown each also has its hall or theatre, in some cases both. Each of these Mr. Du Val has visited. At the Diamond Fields the audiences are very critical, as Kimberley is always full of agents from London, Paris, and the Continental capitals, who expect to get something for their money. In some districts theatrical business was dull, though Mr. Du Val always drew good houses, staying only a few days at each place, and covering an enormous area in a very short time by coach, by rail, and by steamer. But we cannot linger over Mr. Du Val's adventures in South Africa. He has been over the ground before, and has already told the story elsewhere. Showmen do not often visit Mauritius, and Mr. Du Val took it rather as a little pleasure trip en route for Bombay. Of Port Louis, the capital, he gives a graphic description of its sunny shores half-hidden beneath the wealth of tropical foliage, the lovely panorama of white houses shimmering in the blazing sunlight, the spire-like pinnacles which rear their heads far above in the clear air standing erect like a circle of grim sentinels. French is the universal language, even the hotel is French. There are seven morning newspapers and two weeklies to a population of seventy-five thousand. The news is evolved mysteriously, for there is no cable communication, and the mail comes in once a month. The advertisements are inserted free of cost. Mr. Du Val made a three weeks’ stay in Mauritius, visiting the sugar plantations, helping the residents of Curepipe, the suburb, in their annual fancy fair, where dark ladies rival fair ladies in the little theatre to good houses, and called upon the oldest inhabitant, whose portrait we give.

The O.I. is known to be over two hundred years old. On his back vandals have carved their names and cut their jokes, until he is a walking page of history. He is still full of vigour. In Mauritius sugar is under a cloud owing to the bounty system. Many of the old planters have crippled themselves by former extravagances, and have mortgaged their estates. Their place is being taken by new men, who may infuse fresh life and energy into the island. The Creoles are gradually being driven out by the Chinese and the Hindoos. Here, for instance, is the new mosque, which has just been built for the Mussulman inhabitants.

Mr. Du Val stayed a while in Ceylon, while making what was evidently an interesting tour, seeing most of the sights, playing a few times, and taking many beautiful photographs.

Among the Rajahs and Nawabs Mr. Du Val seems to have had a most agreeable time. He was commanded to appear before the Nizam of Hyderabad, for instance. After a picturesque drive through the moonlit tombstones of Golconda, he arrived at the palace at 9 P.M., the hour fixed. He was escorted by one of the officers of State through parallel rows of fierce-looking gentlemen whose bosoms bristled with bloodstained weapons. “The heavy gates closed behind me,” says Mr. Du Val, “and I was a captive. I was taken to an ante-room and reposed on a luxurious divan, sipping some coffee, and waiting patiently for the summons. Half an hour, an hour, an hour and a half passed. It was 10.30 when I heard approaching footsteps. His Royal Highness was ready. I was taken into the spacious court, into which the lattices windows of the zenanas looked. I saw no ladies, but they saw me. My visible audience was the Nizam and one or two members of his Court. He himself is a sickly youth of twenty-two, dressed not in Oriental magnificence, but in a skull cap and a short fawn-coloured jacket. He was much interested in my performance, standing most of the time with one foot on the stage, and between every song looking up and exclaiming, ‘Halloo,’ sometimes as an interjection, sometimes as an interrogative, sometimes as a congratulation. He has eighty wives.”

On another occasion Mr. Du Val was engaged by a Nawab of Hyderabad to give an entertainment at a very gorgeous reception. The gardens were like fairyland, the band was composed of lovely Amazons in Khaki uniforms. The open air theatre was placed in front of the Durbar Hall, flanked by palm trees, lit by electric lamps and coloured lanterns. The Nawab, ablaze with jewels, sat in the midst of his five hundred guests, The Nautch girls chanted, the Amazons played, and the time drew near for Mr. Du Val to begin. Suddenly he received a message from the Nawab suggesting that he should give his entertainment in the midst of a magnificent display of fireworks, which had been prepared on an elaborate scale – but was intended as a single item in the evening's amusements. The Nawab had paid his money, but Mr. Du Val, though he has aspirations heavenwards, did not feel equal to the occasion without a longer shrift, and declined politely but firmly. In Bombay he had good houses, playing there three times during his first visit to average houses of £70 0r £80. From Bombay he went on to Calcutta and Madras. Calcutta is not a good pitch from a theatrical point of view, as the theatre-going people live on Malabar Hill, four miles away fro the theatres, and dinner is not over till half past nine, after which people are too lazy to drive in. In Madras Mr. and Mrs. Grant Duff and all the notabilities dropped in to listen to the English showman. At Calcutta he took the theatre for a month, at a cost of a thousand rupees, plus expenses of advertising, gas, and attendance – figures which may give some idea of the outlay of a tour.

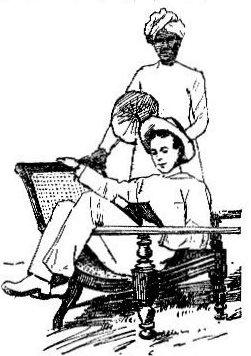

In the course of his travels in India and Africa Mr. Du Val often came across the wrecks of theatrical companies bleaching and rotting in the burning sun – companies of incompetents – X’s Comedy Company, Y’s Jewels, Z’s Minstrels, and so on, poor players who have been stranded in the financial storm. Mr. Du Val found travelling in India very agreeable. He describes the 1,500 miles of railway between Bombay and Calcutta as a journey, not through a tiger-infested jungle, as we picture it here, but as a passage through an English parkland, the vivid green hues or the paddy fields helping to soften the glare of the Indian sun. Here and there he stopped, now at Allahabad, now at Secunderabad, now at military cantonments, with names too elaborate for English ears each of which has its garrison theatre. And everywhere he made friends and was made welcome. Shakespeare is a magic word with the Indian Baboos, who used to come in large numbers to hear Mr. Du Val’s recitals. When Bhuggo Butty Churn Mullick and Bhenod Behazy Mullick gave a grand reception in celebration of the marriage ceremony of the daughter of Baboo Bhuggo Butty Churn Mullick at – heavens ! what an anticlimax No. 90, Cross-street – Calcutta, this Mr. Du Val attended. The bride was about eight, a child in puce velvet encircled by an emerald girdle who sat on a dais shivering like an aspen leaf. The bridegroom was motionless as a wax figure. The ceremony, which took place in a large hall, overlooked by the usual zenana windows, was as pretty as could be desired. The guests partook of champagne and ices, and each one wore a garland of flowers. Madras has been described as the City of Magnificent Distances. The post office is miles away from the hotels, the hotels from the theatres, and the theatres from everywhere else. Theatrically that is not desirable. Mr. Du Val and his assistant took many excellent photographs during their journey. By his kindness we are enabled to reproduce one or two of them here.”

(1) These drawings on brown ground are taken from a poster dated 1 October 1886 advertising a show called "Mr. Charles Du-Val At Home" at the Prince's Hall after Charles Henry Du Val and his team had returned to London.

(2) Du Val Tonight! The Story of a Showman by Vivien Allen (1990) pages 150-156.

(3) Pall Mall Gazette 12 May 1886.

For a collection of the press reports on Charles Henry Du Val see Charles Henry Du Val Press Cuttings.