Charles Allen Du Val

His life and works

Final Overseas Tour

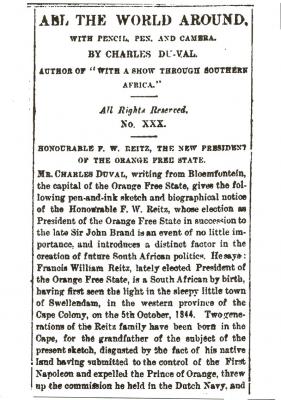

Belfast News-Letter 31 July 1888

By the end of 1887 Charles Henry Du Val was planning a huge worldwide tour 0f his show, starting in South Africa, then on to Madagascar, Mauritius, Ceylon, India, Burma, Malaya, China, Japan and the United States. After that there was to be yet another London season.

Before they set out in 1888, a family photograph was taken.

This time the South African tour was more successful, as the economy there was improving. They met Charles Deecker who had started a new paper, and they went with the Deeckers to Johannesburg. Reports went back to the press at home.

The Belfast News-Letter 21 September 1888

The Belfast News-Letter 1 January 1889

While in Johannesburg Charley fell ill again for a time. By the time they reached Durban to take ship east, he privately admitted that he was worn out. On the voyage to Ceylon he began to show signs of a breakdown, and by the time they reached Colombo he had to abandon the remainder of the world tour.

Despite his illness, however, he continued writing and sending press reports back to England as he had promised.

On the voyage home through the Red Sea, Charles Henry Du Val disappeared from the ship.

On the day before he died, Charley had been indisposed but seemed to be recovering. He was his usual cheerful self and ate a good dinner.

During the night he felt unwell. Minnie was sufficiently alarmed to awaken a member of their party, Fred Carter.

Suddenly Charley dashed up the companionway and on to the deck. Thinking he just needed a breath of cool air, Carter followed him at normal pace. But when he reached the deck Charley had vanished. The captain was called out, and soon it was all too painfully clear that Charley had gone overboard. And it was too late to turn back. It was 23 February 1889.

A press reporter on board concluded that it was suicide, but Minnie, Carter and the captain all thought it was an accident. The rail was low, and in places there was only a rope at the edge of the deck. When the ship reached Brindisi in Italy, the reporter cabled his scoop to London. By the time the ship arrived home, England rang with the suicide story. Minnie was distraught. Carter wrote to every major publication

“Having just arrived home after the tour on which I started in company with Mr Du Val, I am pained to hear that a cruel report has been circulated with regard to his death. As the close friend and fellow traveller of the deceased, I trust you will allow me to state the true facts of the case.”

But it was too late. People believe what they read in newspapers.

The Du Val family were horrified. Suicide was a terrible disgrace in those days. They never spoke of Charley again, and he was wiped from their collective memory. Minnie moved to a smaller house, and soon lost all contact with the Du Val family.

Madeline went to stay with them sometimes, but Minnie never saw them again.

Charley had left £3,385 after all debts were paid – a substantial sum, and over three times what his famous artist uncle had left. So he had provided well for his family. Minnie Du Val died from a stroke aged 66 in May 1914. Madeline followed her father on to the stage, but with little success. She married Harry Eglinton Bowes, and lived to be 92. She had no children, and died in June 1970.

The huge benefit performance in London marked the grief of his fellow artistes:

The tragedy of Charley’s death echoes through several levels. It was a personal grief for Minnie and Madeline, and a disaster for the wider Du Val family. The stage had lost a talented showman, poet, musician, and the world a great entertainer. But there are broader implications. Charley Du Val was only 42 when he died, and had many years before him. His dramatic readings and opera burlesques spanned the world of Charles Dickens and the Savoy Operas. He could have been a renowned composer and influential writer. He was as biting a satirist as Gilbert. As passionate a social reformer as Dickens. And more diplomatic than both.

But is there a still greater tragedy?

His first-hand knowledge of South Africa, coupled with his access to powerful people at home, might have slowed down or even halted the dreadful disaster unfolding in that country. The Manchester Guardian alone among the major English press opposed the Boer Wars, but Charley Du Val might just have prevented them. And saved countless lives. He knew too that Germany was slowly infiltrating British interests in Africa, and he wrote tellingly against them. Had Charley Du Val lived, might not the gilded Edwardian age have been otherwise, and the dreadful disasters of two world wars have been avoided?