Charles Allen Du Val

His life and works

The Great Entertainer In South Africa

RMS Nubian

Charles Henry Du Val and his wife Minnie sailed from Southampton on 20 November 1879, among sleet and biting wind. The ship was the pride of the Union Line, but they had a rough passage. After making shore trips to Madeira and St Helena they disembarked safely at Cape Town on 17 December 1879.

They stayed there at the Masonic Hotel, as Charley was a freemason. However the town was plagued with mosquitoes. “They have drains and dogs, too, in Cape Town,” Charley wrote. “The former are open, offensive and typhoid-producing, the latter are nondescript, mixed and indescribable.” So were the human inhabitants, of all manner of races and tongues. Once he met a singing group, and went nearer to hear some “curious old Oriental ballad or Paynim chant”. But the melody was all too familiar: “My Grandfather’s Clock, by everything that’s dreadful!”

Seeking copy for his press obligations, he interviewed Cetshwayo, the exiled Zulu king. Through an interpreter the king told Charley that he had never wanted to fight the British, but had to defend his people when attacked. He longed to return home with the five wives he had been allowed in exile. Charley thought that “he was suffering from loneliness owing to the absence of the rest of the Mrs Cetshwago”.

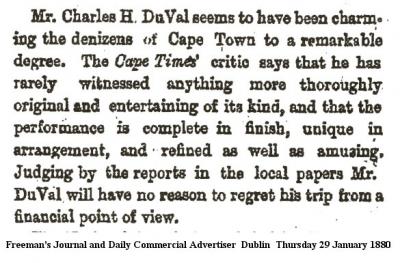

His Christmas one-man show was wildly successful, and he closed with a seasonable song The Wassail Bowl, of which he had written the lyrics and composed the music. By changing the programme, he got people to come back for several performances. The season closed with a performance at the Open Air Theatre accompanied by the band of the 91st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Their captain performed in drag with Charley to rave reviews.

On 16 January 1880 Charley and Minnie left Cape Town by train for Kimberley. On the journey they had to stay overnight at a station hotel. Next day, after travelling eight miles, the train stopped and went back again. Charley discovered that

“ - the guard of the train had been left behind; the fascinations of either the barmaid or her wares had been too many for a heart which even continual railway travelling had not entirely reduced to a fossil, and the other officials, regarding him I presume as of ornament rather than use, sent the train on its way rejoicing.”

At the next stop, contrary to what they had been told, they found the railway still not completed.

“To keep up this interesting fiction, we transferred ourselves and our baggage into two open trucks and whirled along the unopened line for two hours under the blazing sun.”

Then they had to stay overnight again and transfer to wild west stage coaches, with two overnight stops in Boer farmhouses, to reach Kimberley.

In his book Charley Du Val gives a full account of the diamond mining at Kimberley, and the dubious political manoeuvres that had taken place. The heat and working conditions were terrible. The corrugated-iron roof of the hotel made life inside unbearable until it cooled in the evening. But there was plenty of social life, and for three weeks Charley packed the new Theatre Royal with performances of his show.

For travelling beyond Kimberley Charley bought a covered coach and four horses, with two more for their wagon and a riding horse for himself. He fitted folding beds in the wagon for Minnie and himself, with baggage space. On the outside of their wagon tent he painted “DU VAL TONIGHT!” Thus equipped they set off on their journey “with a show through Southern Africa”.

They were totally unprepared for the hazards ahead – no bridges over raging streams, and endless dust or mud. The vehicles continually broke down. Yet despite many hair-raising mishaps, Charley never lost his sense of humour. It was certainly no life for an invalid, yet Charley thrived on it. Wherever they went Charley, Minnie, and the show, were a great success.

By May 1880 they were in Port Elizabeth, where they saw Empress Eugenie of France visiting the grave of her son, the Prince Imperial, killed fighting alongside the British. Charley recalled another occasion when he had seen the Empress:

“A good many years ago, a somewhat forward boy, I crushed my way through the crowd surrounding her carriage, opposite the Queen’s Hotel, Manchester, and shouting the words ‘Vive Eugenie’, received a graceful acknowledgment from an elegant-looking woman, whose face was mantled by a bright blush, and who smiled as she recognised an oft-repeated cry which echoed and re-echoed through the streets of Imperial France of that day. The picture was a good deal changed now -“.

Charley and Minnie attended a regatta. It was to be their last outing together in South Africa for many years. The RMS Nubian was in port, and Minnie returned to England. Their son Rupert was born in their Dublin home on 20 September 1880. Charley was now alone in South Africa.

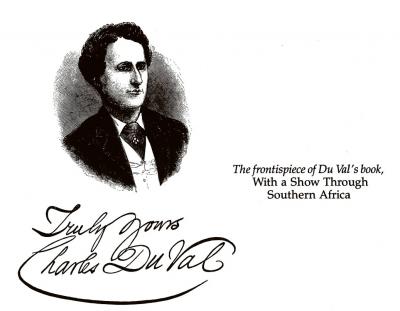

This account of the travels of Charles Henry Du Val and his wife Minnie is based on his own book With a Show through Southern Africa and Personal Reminiscences of the Transvaal War. (The one-volume popular edition published for the South African market in 1884 has been used.)

Information has also been added from reliable contemporary newspaper cuttings.