Charles Allen Du Val

His life and works

Samuel Bough

Samuel Bough was born on 8 January 1822 in a small house at the poorer end of Abbey Street in Carlisle. His father was a shoemaker, but had served as valet in Bath to an army doctor Sir John Dacre Appleby Gilpin, and his mother nee Lucy Walker had been a kitchen maid in the same household. They had married in St Mary's church within Carlisle cathedral on 18 January 1818.

After a haphazard childhood and little formal education, he showed early artistic talent. As a painter however, he was self-taught. He went to London and soon became recognised as a fine draughtsman and artist. He returned to Carlisle and ventured on productive sketching trips through the Border Country and the Lake District. In 1844 he exhibited for the first time at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. However his career took a new direction when he went to Manchester to work as a theatre scene painter. There he joined other artists in setting up The Manchester Academy of Art, whose first president was Charles Allen Du Val.

However he realised that he would never make a successful career in Manchester, and moved to Glasgow as the principal scene painter at a new theatre. There he married Bella Taylor on 30 April 1849, and gradually returned to serious painting, exhibiting at The Scottish Academy. The couple settled in Hamilton, where Sam continued to paint landscapes, with some theatre work to increase his income. Later they moved to Port Glasgow, but eventually and inevitably they settled in Edinburgh. There he followed Turner in becoming a masterly painter of seascapes. His work was greatly admired, not least by his friend Robert Louis Stevenson, for whom Samuel Bough painted a view of his house at Swanston, and also a picture of a lighthouse under construction by Stevenson's father and uncle.

Sam Bough died at his home Jordan Bank in Edinburgh on 19 November 1878.

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of him (1):

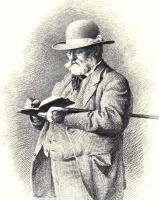

"This is not only a loss to art, but the disapperance of a memorable type of man. Spectacled, burly in his rough clothes, with his solid, strong, and somewhat common gait, his was a figure that commanded notice even on the street. He effected rude and levelling manners; his geniality was formidable ... and he delivered jests from his shoulders like bullets. He loved to put himself in opposition, to make startling, and even brutal speeches, and trample proprieties under foot. But this, although it troubled the amenities of his relations, was no more than a husk, an outer man, partly of habit, partly of affectation; and inside the burr there was a man of warm feelings, notable powers of mind, and much culture ...

It was a sight to see him attack a sketch, peering boldly through his spectacles and, with somewhat tremulous fingers, flooding the page with colour; for a moment it was an indescribable hurly-burly, and then chaos would become ordered and you would see a speaking transcript; his method was an act of dashing conduct like the capture of a fort in war. I have seen one of these sketches in particular, a night piece on a headland, where the atmosphere of tempest, the darkness and the mingled spray and rain, are conveyed with remarkable truth and force. It was painted to hang near a Turner; and in answer to some words of praise - 'Yes, lad,' said he, 'I wasn't going to look like a fool beside the old man.'"

(1) The Academy 30 November 1878.